Who We Are

Portraits and Vernacular Photography

6/9/2024 — 3/30/2025

6/9/2024 — 3/30/2025

Who We Are is the first part in a three-year exhibition survey dedicated to vernacular photography, the broad category of everyday images we are most familiar with and those that define our lives. The variety of material and creative forms of vernacular photography are seemingly infinite. Some of the general categories included in this exhibition are family photography and snapshots, photo albums and displays, ethnographic and scientific photography, mug shots and identification photographs. What unites these photographs is not an aesthetic or a style but a function, they are utilitarian and purposeful.

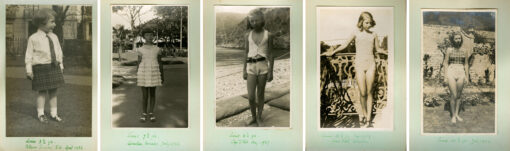

This exhibition looks specifically at vernacular photographic likenesses and the daily cultural factors that shape individual and collective subjectivities. Like conventional portraits, these humble vernacular images demonstrate the modernist fascination with identity, the individual, and the human face. But unlike historical portraiture, these commonly made pictures serve a variety of practical, personal, commercial, and bureaucratic purposes. They eschew the idealized attributes of individuality, self-reliance, and psychological interiority associated with modernist portraits, while demonstrating socially inflected markers of race, class, gender, sexuality, and status.

Divided into five thematic sections, Who We Are is displayed throughout the four exhibition buildings of The Walther Collection: “Against Portraiture” downstairs and “The Photographic Object” upstairs in the White Cube; “Decolonized: Changing Visions of African Identity” in the Green House; “Photo Albums: Archiving Everyday Life” in the Black House”; and “Ways of Gender Identity” in the Gray House. While not comprehensive, these focused case studies offer original ways of seeing familiar images and new perspectives on quotidian social histories.

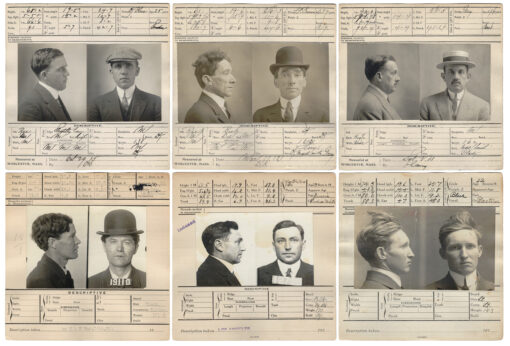

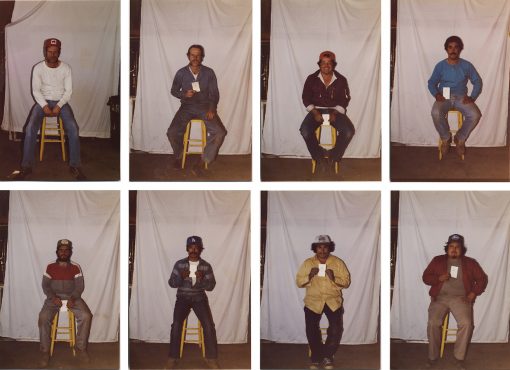

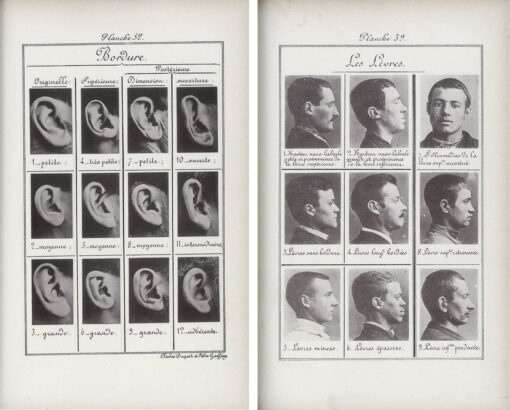

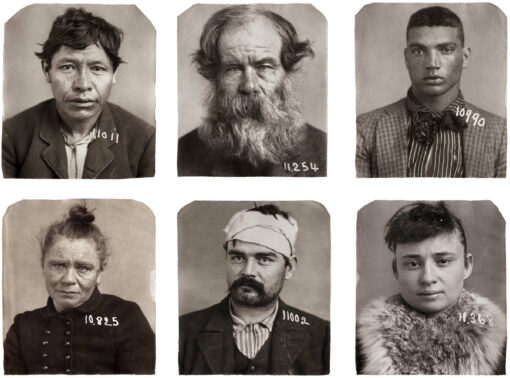

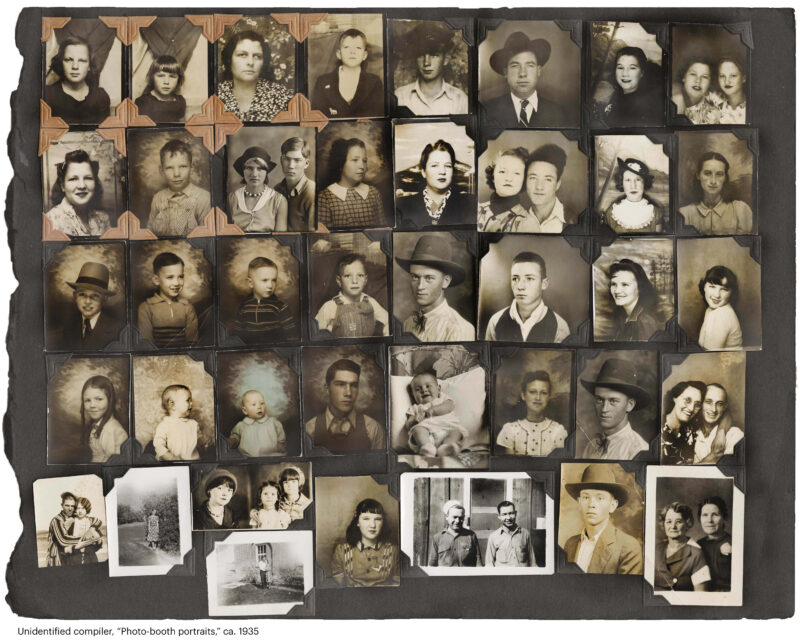

Traditionally, painted and photographic portraits have been considered as honorific markers of social status. The presentation in the main exhibition space of the White Cube reconsiders the portrait in relation to vernacular photography, and suggests that not all photographic likenesses can be considered as traditional portraits. Rather, what might be called “identification photographs” are simply records of human faces compiled to situate individuals within social hierarchies and bureaucratic archives, from the family record to the police mugshot. Such identification photographs have long been used to sort, shape, segregate, and categorize citizens based on occupation, social group, body type, or political affiliation.

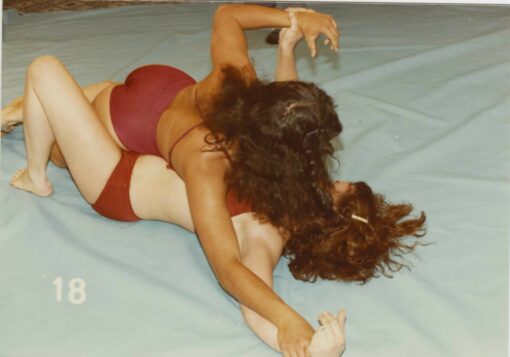

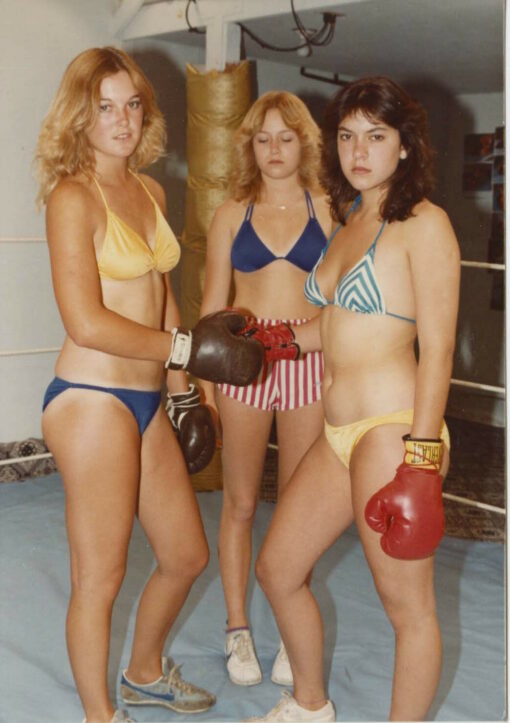

Across five thematic sections—Family, Labor, Play, Types, and Regulation—this installation reorients the viewer to different questions pertinent to the uses of identification photographs, including changing notions of work and leisure, gender and sexuality, and race and ethnicity. Looking at how individuals are represented and positioned within specific social systems questions both the uniqueness of the conventional portrait and the notion of a stable, authentic self.

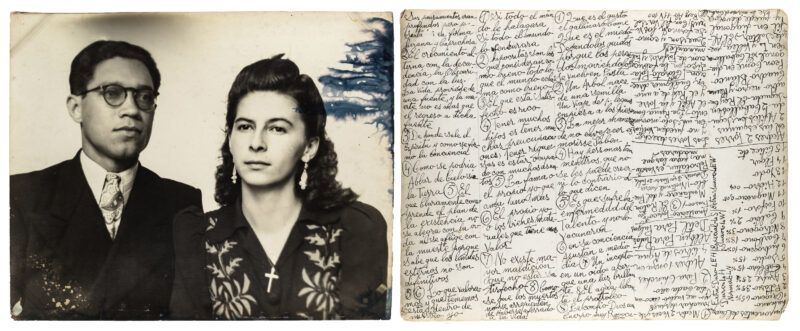

Families, the bedrock social unit of the modern era, were fortified by the new capacity for photographic representation. Either as group sittings or as collections of individual portraits, photography allowed families to memorialize their genealogies in a single frame or family record. Later, the family photo album evolved as the universally accepted, twentieth-century vehicle for the personal and creative narration of family gatherings, rituals, travels, and events, and as a means of communal expression and domestic self-definition.

Nineteenth-century workers and craftsmen often posed proudly with the tools of their trade in studio photographs and tintypes. These occupational images were signifiers of social and professional status. Later, photo-based identification cards, ID badges, and licenses were typically required at sites of employment, especially where issues of security and surveillance were involved. But workers also frequently desired group photographs that represented their collective labors and group identification, as with the Appalachian coal miners gathering for panoramic photos.

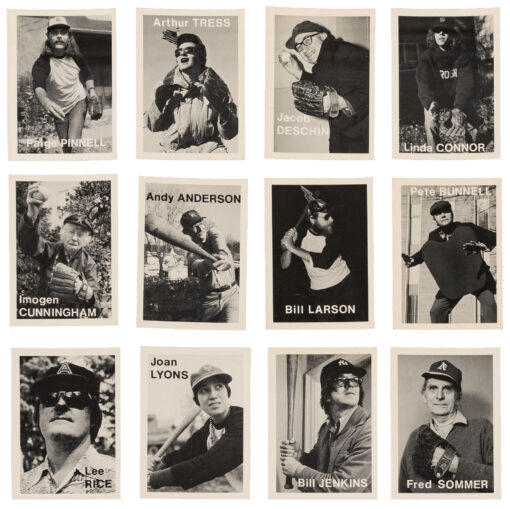

Photographs provide detailed documentation, but they also provide entertainment. They can capture celebrities and performers, as well as daily fun and games. Even before the advent of popular photography in the 1890s, sitters played a significant collaborative role in establishing their self-expression and cultural identity in the photographic likenesses. In studio settings, customers were able to pose, with pride or humor, in clothes and props of their own choosing. At carnivals and tourist venues, photographers sometimes provided cartoonlike drawings to playfully amplify the sitters’ appearances.

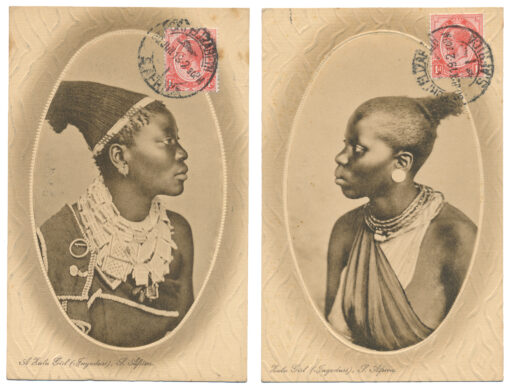

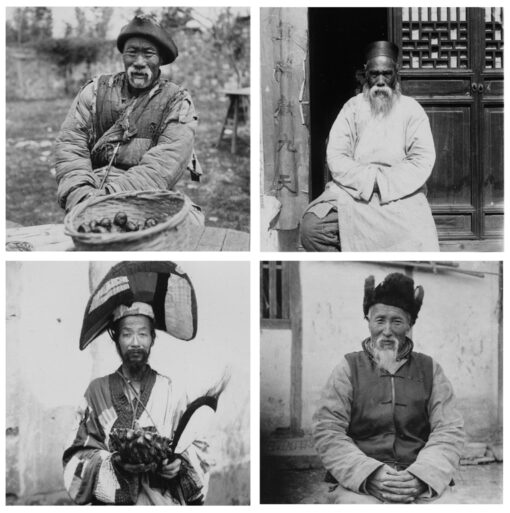

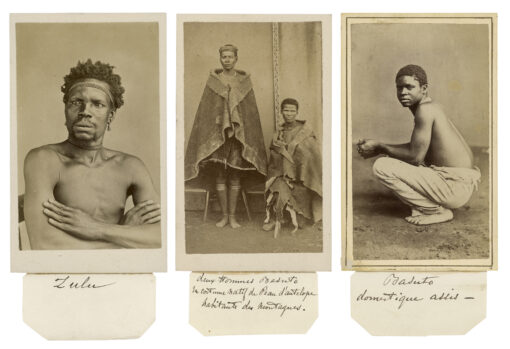

One way of establishing sovereignty over another culture or community is through stereotypical or dehumanizing imagery. In the nineteenth century, anthropologists and social scientists often divided social groups into “types,” classified by racial or cultural similarities and depicted as representative examples. These typological photographs of indigenous subjects were often placed in idealized studio settings or sexualized in the manner of their dress and presentation. In popular culture forms, such as touristic postcards, these “types” were circulated as images representing the whole culture, and as primitivist signs of cultural difference.

Identity photographs and facial recognition are key components of most archives of social regulation and policing. From driver’s licenses to prison mugshots, the standardized headshot allows one image to be compared to another based on physiognomic differences. For such identity photographs, the character or personality of the sitter—the hallmark of the bourgeois portrait—is irrelevant. Mug shots, such as the ones included in this exhibition, were invented as a comparative model of facial recognition and body forms, used to predict criminal types and to judge one individual’s character against another or against a statistical median.

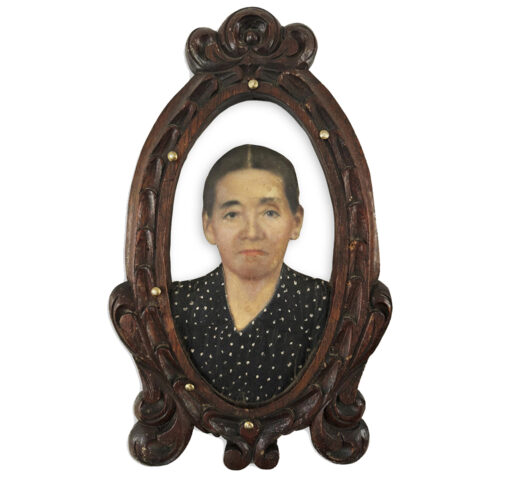

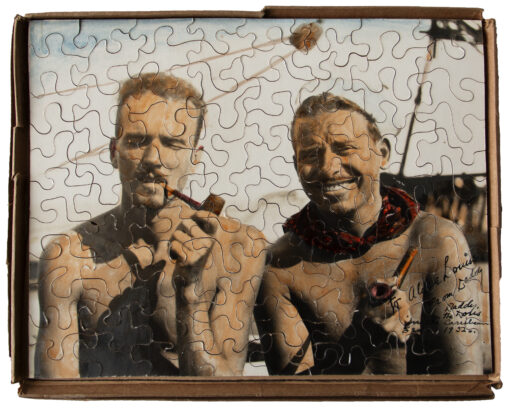

In its physical form, the photograph is more than an image. It is also the material from which other tangible things can be constructed. The hybrid objects shown here all incorporate or frame vernacular photographs of individuals in some way, including photo-sculptures from Mexico, a jigsaw puzzle, a breadbox full of naughty photos, a heart-shaped ashtray, and freestanding photographic cutouts, called “humanettes.” These inventive objects constitute a form of three-dimensional collage, an adaptation of the ubiquitous photographic image to the specificities of domestic decoration. Made by amateurs or professionals alike, these outsider-art-like objects retain a quirky and irreverent attitude toward portraiture and popular photographic imagery.

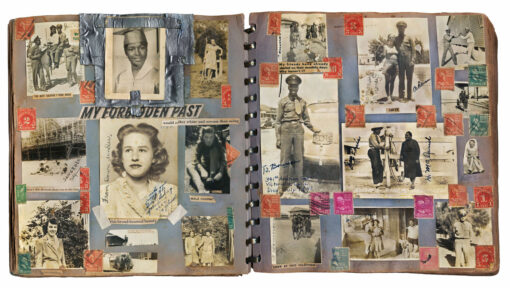

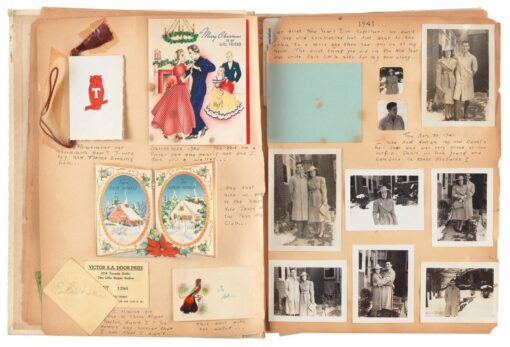

Photo albums are compelling historical artifacts elucidating the intricate processes by which individuals curated and projected their personal narratives and identities through visual media. Once amateur photography became widespread in the late nineteenth century, the album developed into the most important medium for storing, collecting, and presenting photographs. However, it was not only used to document significant life events such as weddings, family celebrations, or travel, but also functioned as an instrument of self-representation, facilitating the construction and reinforcement of distinct identities.

As with contemporary social media, historical photo albums often depicted an idealized version of reality, accentuating individuals’ happiest moments, successes, and most flattering appearances while eliding less favorable aspects of their lives. This selective portrayal aimed to stage a positive and aspirational image for external consumption, reflecting desired self-images rather than objective realities.

Photo albums not only serve as a repository for personal experiences, but also document historical events, personal passions, and pop-cultural phenomena, thus providing insights into the political and social climate of their time—often in impressive abundance and depth, which is why these handy image archives are also an important source for historical research today.

Since the advent of mass media in the early twentieth century, photography has profoundly influenced societal perceptions of individual identity and difference. From news coverage to social media platforms, magazines, and advertisements, overabundant images have shaped our ideas of how we should live, look, and behave—especially when it comes to gender identities.

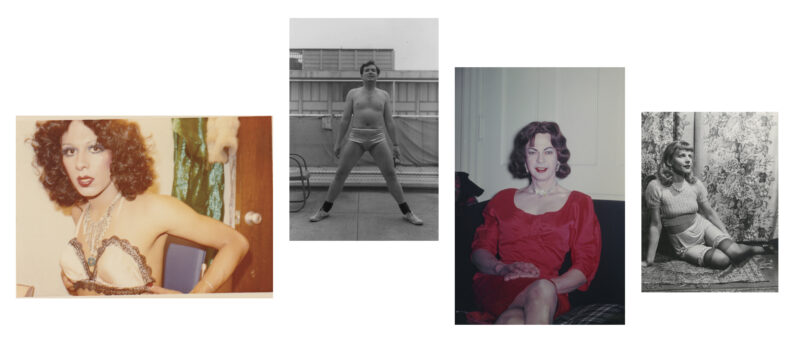

While photography can be an instrument of control and standardization, it can also function as a platform and safe space for people who position themselves beyond conventional heteronormative gender roles. The presentation in the Gray House explores three thematic perspectives: “Beyond Stereotypes”; “Self-Explorations”; and “Versions of Womanhood.” These views introduce photography as a critical means to examine and to deconstruct traditional concepts of gender and sexuality.

Marginalized communities, notably those within the LGBTQIA+ spectrum, often employ photography as a tool for self-empowerment. Through self-portraiture, individuals assert control over their own narratives, contesting stereotypical depictions of gender and sexuality, and offering alternative perspectives that celebrate diversity and inclusivity. Such self-portraits support personal development based on individual needs, providing individuals with opportunities for both introspection and self-assurance. Although these self-representations sometimes reproduce the sexually suggestive poses that are used time and again in mass media, they also challenge the mainstream binary gender system by emphasizing the performative character of sexuality and gender.

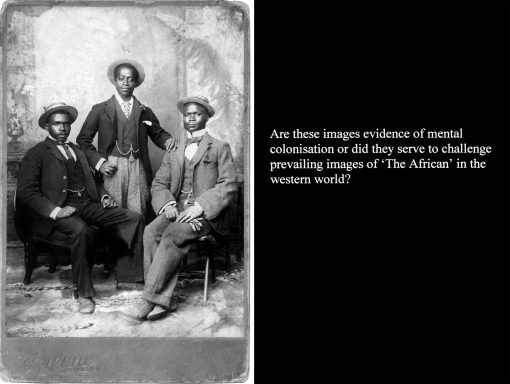

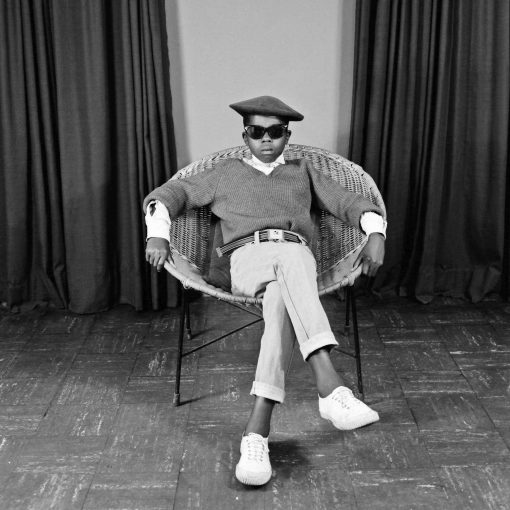

Photographic representations of African subjects have shaped how they are seen by others and how they see themselves. Looking at aspects of African identity within the context of European colonialism, this presentation considers four historical moments—mid-nineteenth-century cartes de visite made by European photographers, early twentieth century postcards illustrating African “types” to European audiences, the liberatory Apartheid-era portraits of S. J. “Kitty” Moodley, and the 1997 slideshow of contemporary photographer Santu Mofokeng titled The Black Photo Album / Look at Me.

In The Black Photo Album, Mofokeng provides a methodology for reflecting on the historical uses and contemporary meanings of vernacular photography. Juxtaposing found family photographs from the early twentieth century with contemporary critical questions, Mofokeng asks, “Are these images evidence of mental colonization or did they serve to challenge prevailing images of ‘The African’ in the western world?”

In dialogue with Mofokeng are earlier historical images of African subjects staged by colonial photographers and the astonishing studio portraits taken by photographer “Kitty” Moodley in South Africa in the 1970s, during Apartheid. These portraits portray poor and working-class patrons playing with traditional and modernist modes of dress and displaying cross-cultural challenges to socially accepted family, ethnic, and gender roles.

Who We Are: Portraits and Vernacular Photography is the culmination of the The Walther Collection's exploration of vernacular photography through the multi-year exhibition series “Imagining Everyday Life: Aspects of Vernacular Photography” at the Collection’s former Project Space in New York from 2017 to 2019, curated by Brian Wallis; a two-day international symposium at Columbia University in 2018; and a major scholarly catalogue, awarded the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation prize for Photography Catalogue of the Year in 2020.

In 2018, The Walther Collection, with The Center for the Study of Social Difference at Columbia University and The Barnard Center for Research on Women, presented a two-day symposium entitled Imagining Everyday Life: Engagements with Vernacular Photography. The symposium articulated the multiple definitions of vernacular photography within a newly expanded field of critical investigation, reconsidering the context and meaning of often overlooked photographic practices and tracing their specific social histories. Bringing together speakers from a wide range of academic disciplines, presentations considered vernacular photography in diverse stylistic forms, utilitarian applications, and regional variants. With examples ranging from ethnographic records to criminal mugshots to family photo albums, the discussions offered new ways to think about photography in relation to our political communities, social agency, and daily personal rituals.

Participants included: Ariella Azoulay, Geoffrey Batchen, Ali Behdad, Elspeth H. Brown, Tina M. Campt, Clément Chéroux, Lily Cho, Nicole R. Fleetwood, Sophie Hackett, Patricia Hayes, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Thy Phu, Leigh Raiford, Shawn Michelle Smith, Drew Thompson, Brian Wallis, Laura Wexler, and Deborah Willis.

Edited by Tina M. Campt, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, and Brian Wallis

In this major catalog dedicated to vernacular photography, the authors reevaluate the agency of the makers, compilers, subjects, and viewers of vernacular images and highlight the social roles they play. These new approaches recast existing histories of photography and insert into those narratives objects and questions that have been in large part ignored or erased.