Photography and Transformation in Urban China

At this time, 94 percent of the Chinese population lives in big cities, all located in the eastern part of the country. The other parts of the country have become increasingly deserted; as recently as the early 1980s, a large part of the Chinese population lived in rural areas. Such rapid urbanization was a result of the economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997). These initiatives were intended to stimulate the country's growth, which is why the government pushed the transformation of cities into major industrial metropolises, especially in the 1990s.

The transformation of urban space is an important topic in Chinese art, and many artists today use photography to depict the structures of the modern megalopolis. It seems that this medium is perhaps better suited than others to reproduce the smooth facades and outsize dimensions of the monumental skyscrapers. Such images, however, are not new: photographers have dealt with the theme of urbanization since the advent of the medium. Charles Marville (1813–1879), for example, famously recorded the modernizing transformation of Paris in the nineteenth century, stewarded by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, which the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–1827) often lamented:

"Old Paris is no more (the form of a city

Changes more quickly, alas! than the human heart)"

– Charles Baudelaire, "The Swan", The Flowers of Evil, 1857

In the meantime, New York, with its dizzying high-rise architecture, has become the epitome of the modern metropolis. The skyline view of Manhattan has degenerated into a popular postcard and poster motif—now almost ordinary and banal. Perhaps the megapolis of the 20th century has lost its sensational allure, at least in the USA and Europe, but the same is not true of images of Chinese cities, which still attract a lot of attention. But why? Perhaps because of these cities' unprecedented size and demographics: images help us to understand how 27 million people can live in Shanghai or 34 million people in Chongqing.

How do these images manage to arouse our interest? What do Chinese photographers think about this metropolis-centric representation of their country? And what place do such photographs have in The Walther Collection? A comparison of the works of the German photographer Michael Wolf and the works of Chinese photographers from The Walther Collection will examine the questions in more detail.

Michael Wolf, who died in April 2019, was not a foreigner in China: he had lived in Hong Kong since 1994 and spent most of his career as a professional photographer in Asia. He was interested both in the architecture of the big cities and in the people who inhabit them. For example, the series "100 x 100" explores how people manage to adapt to these often narrow, hectic and crowded environments. "Tokyo Compression" also impressively depicts the lack of space in the Tokyo subway.

Many Chinese photographers dealing with the theme are represented in The Walther Collection, and live in different megacities in the country: Luo Yongjin and Xiang Liqing live in Shanghai, Miao Xiaochun and Zhang Dali in Beijing, Weng Fen and Yang Yong in Shenzhen. They are between 44- and 59-years-old and experienced the dramatic change of these Chinese cities as young adults. An exception is Sze Tsung Leong, who grew up outside China and now lives in the USA. Although the photographers examine the same subject, each of them deals with it in their own unique way.

To add visual interest, many photographers choose unusual formats and perspectives. For example, panoramic images are common to show the vastness of a city. Photographs from a worm's-eye view taken from below looking up are also widespread. Both viewing angles make it possible to show the buildings in their entirety and emphasize the dimensions of the objects. They give the viewer the impression of being a Lilliputian in Gulliver's world.

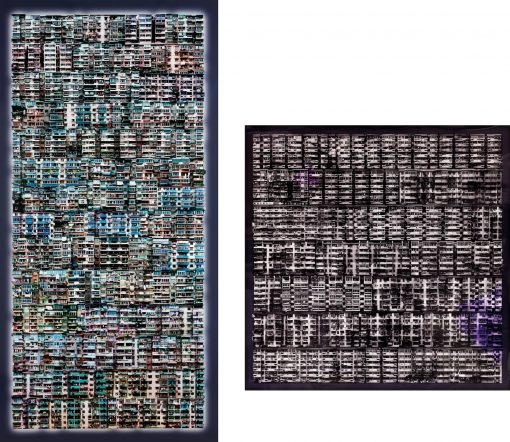

Michael Wolf's photographs deviate from these well-known staging strategies, as he only photographs parts of buildings. Wolf fades out the horizon, and it seems as if the buildings are endless. Anyone looking at his photographs feels the claustrophobic narrowness of Chinese cities. The view of these buildings is hypnotic: it's easy to forget that this is a city in which millions of people live. The windows seem so small that they seem like mere holes on a concrete surface, abstracting the living space of many people into a graphic structure.

With their conceptual photomontages, Xiang Liqing and Luo Yongjin create fictitious reconstructions to capture a view of Chinese cities beyond the documentary. For Rock Never 1 (2002) Xiang Liqing digitally stacked the buildings of a slum in Hangzhou, where he himself studied and lived, creating a very tall building that doesn't actually exist. Luo Yongjin photographed the various construction phases of the Lotus Block (1998–2002) and then combined the images into a single composition that represents a kind of time-lapse. With a length of four meters, the grid of 60 individual shots cannot be grasped at a glance, which creates a parallel to the immensity of the city.

With its strong color and seemingly perfect view of the Hangzhou facades, Xiang Liquing's Rock Never 1 (2002) could be an advertisement for new apartments in Chinese cities. But nothing is real: the building does not exist and the artist has manipulated the images to paint the facades and personalize the balconies. Indeed, it is easy to imagine that life in Chinese cities can be anything but cheerful. Another picture by Xiang Liqing entitled Grey (2000) is similarly structured, but shows all the buildings dyed a drab shade of grey to refer to the monotony and gloom of everyday life in the big city. The artist also seems to be questioning the principle of the standardization of apartments, recalling Le Corbusier's "Unités d'habitation" throughout Europe in the 1930s and 40s.

Zhang Dali, a famous figure of Chinese street art, also deals in a unique way with the theme of urban transformation. First he spray-paints and chisels a human profile onto the walls of buildings slated for demolition, then photographs his intervention. He invites the viewer to be aware of the danger that destroying these buildings will destroy a piece of China's cultural identity. At the same time, the drawing of the face is a means for the artist to refer to the human tragedies associated with forced resettlement, to create a community of solidarity in the face of these upheavals, and to emphasize the alienating character of the megapolis. These photographs are often the last traces of these buildings.

They recall the photo series "Future Memories" by the Ethiopian photographer Michael Tsegaye, who documented the structural transformation of Addis Ababa in order to capture street scenes and habitats that will soon belong to the past.

The destruction of urban structures has a long tradition in China. Sze Tsung Leong explains this as follows: "In China, history has been defined by the successive erasures and rewritings of the past". During the empire, for example, it was customary for enemy dynasties to completely destroy newly conquered cities before rebuilding them. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao wanted to demolish the forbidden city as a relic of a past system of rule. Against the backdrop of the massive transformation of Chinese cities over the past two decades, all these views, which capture the destruction of old and the construction of new structures, have the value of a historical document.

As such, it is interesting to wonder about what comes next, after decades of construction and the establishment of countless modern metropolises throughout China. Weng Fen's photograph of two schoolgirls admiring a modern cityscape in peace seems to represent a kind of utopia. But what might the two girls say? They are too young to know the former shape of Chinese cities. Are they aware of all the upheavals that the construction of such a city has brought with it?

Urban change in China is one of the themes of the exhibition Then and Now: Life and Dreams Revisited, which will be on view in Neu-Ulm until October 27, 2019.

– Laura Weber

We thank Barbara Wolf for granting permission to use Michael Wolf's photographs in this blog article. © Michael Wolf Archive and Estate.