The Shadow Archive

12/7/2017 — 3/31/2018

12/7/2017 — 3/31/2018

The Shadow Archive: An Investigation into Vernacular Portrait Photography initiates The Walther Collection's multi-year exhibition series devoted to vernacular photography, entitled "Imagining Everyday Life: Aspects of Vernacular Photography." Presented thematically from 2017 to 2021, the series surveys a wide range of historical and contemporary works, in order to investigate the myriad uses of vernacular photography.

Presenting a number of case studies, "Imagining Everyday Life" attempts to delineate general characteristics, establish conceptual categories, and propose various modes of future critical inquiry. The series will include five exhibitions in New York and an international scholarly symposium in Fall 2018, culminating in May 2021 with a comprehensive exhibition organized by Brian Wallis at The Walther Collection in Neu-Ulm, Germany, and accompanied by a catalogue co-published with Steidl.

"Imagining Everyday Life" argues for an expansive definition of vernacular photography as being all photographic expressions used by individuals to demonstrate social truths for culturally specific proscribed purposes. Rather than focusing on aesthetics, this view of vernacular photography concentrates on communal or ritual behaviors. It encompasses a broad social history, spanning from 1839 to the present, and retains a global scope, with particular attention to South Africa and the United States.

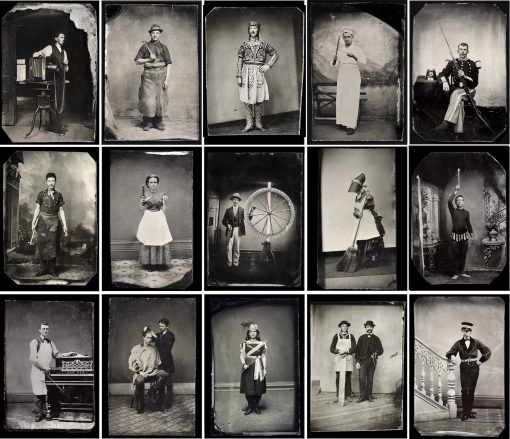

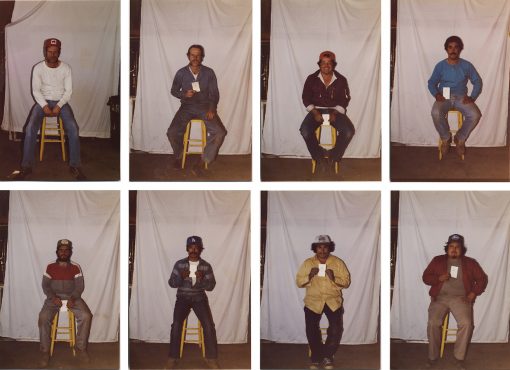

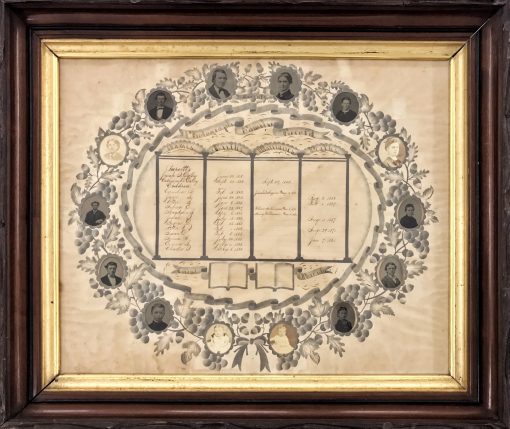

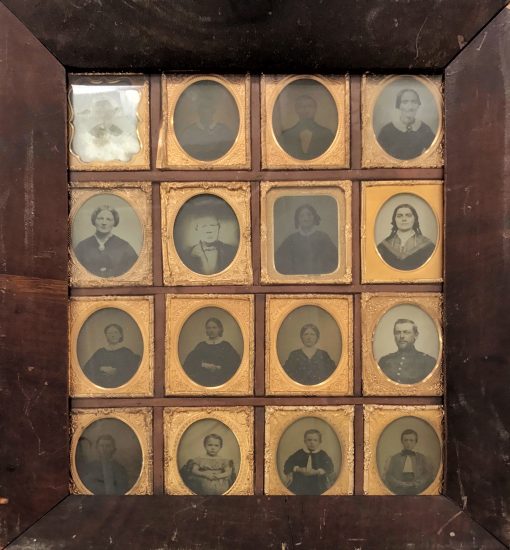

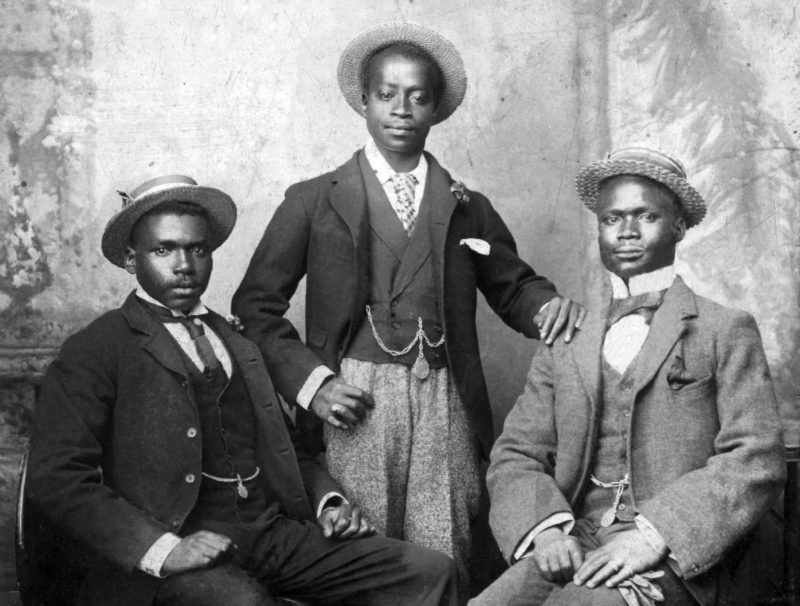

The inaugural exhibition, The Shadow Archive, shows that nineteenth-century daguerreotypes of families to recent images of migrant farm workers, identification photographs have been used to sort, shape, segregate, and select subjects based on occupation, social group, body type, or political affiliation.

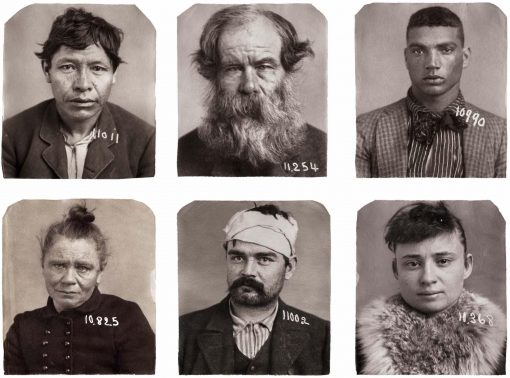

Covering a wide range of historical and contemporary objects, The Shadow Archive includes a frame of sixteen tintypes from the 1860s of family members united to form a visual genealogy; a group of mug shots drawn from an archive of thousands of similar images from California prisons in the 1890s; a sequence of views of a French medical patient demonstrating human emotions while under hypnosis; a collection of eighty near-identical ID badges from a World War II-era manufacturing plant; a roll of dozens of 1950–90s yearbook portraits from a Midwestern high school; and a series of recent color passport-style portraits from a Ugandan studio, all with the faces cut out.

This exhibition asks: can such utilitarian images be considered portraits? What do they reveal of the sitters and their social roles? And what do they tell us about the significance of photography and representation today?

Taken for a wide variety of purposes, these photographs place little value in originality, variety, or aesthetic niceties of photographic style. Rather, they deliberately replicate, and in fact rely on, the conventions of the studio portrait genre. When applied to bureaucratic archives, such photographs establish an inventory of nearly identical pictures that can be compared to one another for identification within a state or corporate organization—as with mug shots in the penal system or passport photos for immigration. The social and even political needs of the sitters—barely discernible signs of resistance, made evident through slight changes of pose or gesture—come to mean more in such contexts than the motives of the photographers.

These pictures defy the bourgeois definition of the portrait as an honorific presentation or a window into the soul. Instead, they are more like fragments from what theorist and photographer Allan Sekula called "the shadow archive." By this, Sekula meant the entire social field of human representations, comprising both heroes and deviants, within which every portrait takes its place as part of a moral hierarchy.

The various, mostly unidentified individuals represented in these portraits, often in relation to their labor and employment, take up positions that are ratified or confirmed by their documentation in photography. Such serialized images lack meaning individually, and assume relevance only in relation to one another, and to the shadow archive.

"...the book is not a reader—instead, the volume perfectly summarizes the status quo of an ongoing discussion about professional and amateur, artistic, and vernacular photography."

Vernacular Portrait Photography at The Walther Collection Project Space